Neural Machine Translation of the Cambridge meme

ICLR 2018 - 2nd article

In this series, we explore the 2018 edition of the International Conference on Learning Representations. Oral papers are analyzed and commented in an accessible way.

This article is based on the paper Synthetic and natural noise both break Neural Machine Translation by Yonatan Belinkov and Yonatan Bisk.

If you are reading these lines, there is a good chance that you have been wandering the Internet for quite some time now. This means that there is also a good chance that you’ve stumbled upon the Cambridge research meme:

There is even a greater chance that you have, for more or less legitimate reasons, used Google Translate (or even better, its European equivalent, DeepL). Of course, those automated translation systems have improved a lot in the past few years; what was laughable at a couple years ago is now quite reasonable for a number of languages. For simple texts, the translation even feels quite natural, although not idiomatic (try translating “Il tombe des cordes.”, which is the usual French equivalent of “It’s raining cats and dogs.”).

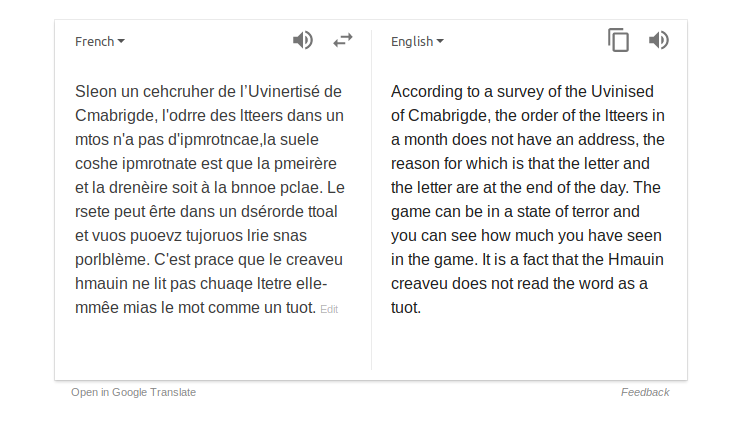

Going back to the meme, you would probably have no trouble translating it to whatever language you are familiar with. But how do automated translation systems cope with this difficult situation? Let’s try translating a French version into English:

| Source | Sentence |

|---|---|

| Original French scrambled |

Sleon un cehcruher de l’Uvinertisé de Cmabrigde, l’odrre des ltteers dnas un mot n’a pas d’ipmrotncae, la suele coshe ipmrotnate est que la pmeirère et la drenèire lteetrs sinoet à la bnnoe pclae. |

| Human translation | According to a researcher at Cambridge University, it doesn’t matter in what order the letters in a word are, the only important thing is that the first and last letters are in the right place. |

| Google Translate | According to an opinion of the Uvinised of Cmabrigde, the name of the ltteers in one word does not have a name, but the name of the message is that the letter and the letter are very brief at the same time. |

| DeepL | According to a cehcruher of the Uvinertized of Cmabrigde, the odd of the ltteers in a word has no ipmrotncae, the only coshe ipmrotnate is that the pmeirere and the drenere lteetrs sinoetrs in the bnnoe pclae. |

This is quite unconvincing, to say the least. In other words, Google Translation and DeepL are both very sensitive to this type of noise, whereas humans seem impressively robust to it. This is just a symptom of the frailty of automated translation systems:

While typos and noise are not new to NLP, our systems are rarely trained to explicitly address them, as we instead hope that the relevant noise will occur in the training data.

It turns out that this kind of wishful thinking leaves Neural Machine Translation (NMT) systems very brittle, with their performance dropping quickly in presence of noise. How can we evaluate this lack of robustness to noise, and what can be done to improve our models? Let’s jump into the paper.

Evaluating the robustness of current models

We would like to evaluate the performance of NMT models, and how it is affected by noise. To do that we will, unsurprisingly, have to answer 3 questions:

- Which performance metric?

- Which NMT models?

- Which kind of noise?

The performance metric: BLEU

BLEU (bilingual evaluation understudy) is a popular metric to evaluate the similarity between the machine translation and a professional human translation. The idea behind it is fairly simple: it is a modification of precision, computed on candidate sentences (by comparison with reference sentences), and then averaged to produce a corpus-level score of the translation’s quality.

Let’s first remember why we don’t use precision as metric for this task. Consider a sentence $s$ to be translated, with human reference translation $r$ and candidate translation $c$. Then precision is a score between 0 and 1 computed as:

[\textrm{Precision}(c, r) = \dfrac{\sum_{w \in W(c)} m_w(c) \cdot \mathbb{1}{w \in W(r)}} {\sum{w \in W(c)} m_w(c)}]

with $W(c)$ the set of unique words that appear in $c$, and $m_w(c)$ the number of occurences of $w$ in $c$. Precision essentially measures the proportion of words of the candidate translation that actually appear in the reference translation. To see why this is not sufficient, have a look at the table below. Usually precision is considered coupled with recall to overcome such issues; we don’t, because recall can be artificially inflated when considering multiple references (see here).

| Reference | Candidate | Precision | BLEU (bigram) |

|---|---|---|---|

| “I like trains a lot” | “I like” | $\dfrac{1+1}{2} = 1$ | $\dfrac{1}{1} \cdot e^{1 - 2/5} = 0.55$ |

| “I like trains a lot” | “a a a a a” | $\dfrac{5}{5} = 1$ | $\dfrac{0}{4} \cdot 1 = 0$ |

| “I like trains a lot” | “I like trains a a” | $\dfrac{5}{5} = 1$ | $\dfrac{3}{4} \cdot 1 = 0.75$ |

| “It is raining cats and dogs” | “It is pouring” | $\dfrac{2}{3} = 0.66$ | $\dfrac{1}{2} \cdot e^{1 - 3/6} = 0.30$ |

To solve those issues, the BLEU score brings a couple of modifications to the precision:

-

Consider the n-grams $G(c)$ instead of the words $W(c)$.

This helps with the fluency of the translation: with words only, “trains lot I a like” gets the same score as “I like trains a lot”. -

Replace $\ \ \textrm{ }m_w(c) \cdot 1_{w \in W(r)}\ \ \textrm{ }$ by $\

\textrm{ }\min (m_w(c), m_w(r)) \cdot {1_{w \in W(r)}}$.

This basically says that, in the second example, only the first “a” will be counted as correct, since “a” appears only once in the reference. -

Multiply by a factor $\ \ \min\left(1, \exp \left(1 - \frac{\textrm{length of reference corpus}} {\textrm{length of candidate corpus}}\right)\right)$.

Indeed, even with the previous modifications, the constructed score still favors short translations (see the first example). We therefore penalize translations that are shorter on average than the reference.

As illustrated in the last row of the table, even with these modifications the final score is not ideal, since a perfectly natural candidate translation gets a low score. It is, however, still much better than precision in a wide range of situations. In the end, the BLEU score takes the following form (the higher the better) for our example sentences:

[\textrm{BLEU}(c, r) = \dfrac{\sum_{g \in G(c)} \min (m_g(r), m_g(c)) \cdot \mathbb{1}{g \in G(r)}} {\sum{g \in G(c)} m_g(c)} \cdot \min\left(1, \exp \left({1 - \frac{\textrm{length}(r)}{\textrm{length}(c)}}\right)\right)]

The NMT models: Nematus and char2char

This will be much quicker. We want to see how state-of-the-art models with different architectures (and especially different accesses to words, sub-word units or characters) are able to cope with noise. The authors ran their experiments on three distinct models:

-

char2char (Lee et al., 2017) - a sequence-to-sequence model with attention, trained on characters to characters (implementation).

-

Nematus (Sennrich et al., 2017) - a competition-winning sequence-to-sequence model with some architectural modifications that enable operating on sub-word units (implementation).

-

charCNN (Kim et al., 2015) - an attentional sequence-to-sequence model based on a character convolutional neural network. To quote the authors, “this model retains the notion of a word but learns a character-dependent representation of words”, and “performs well on morphologically rich languages” (implementation).

The noise types: Nat, Key, Swap, Mid, Rand

We finally need to define a number of noise types that we will use to perturb the models.

| Source | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Original | weather | Original correct word |

| Nat | whether | Natural noise, e.g. spelling mistake |

| Key | qeather | Replace a letter with an adjacent key (QWERTY keyboard) |

| Swap | wetaher | Swap two letters except the first and last ones |

| Mid | whaeter | Scramble the letters except the first and last ones |

| Rand | raewhte | Scramble all letters |

Facing the truth - the (in)ability to translate noisy texts

With all the tools in hand, it is now time to experiment and face the truth: how well are our NMT models able to cope with the different noise types? I’m definitely too lazy to run all the tests by myself, so I’ll steal the paper’s results instead.

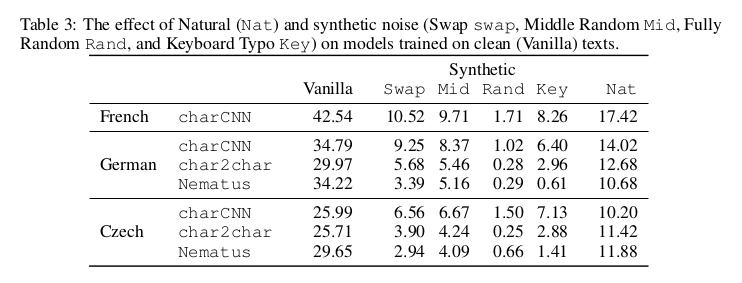

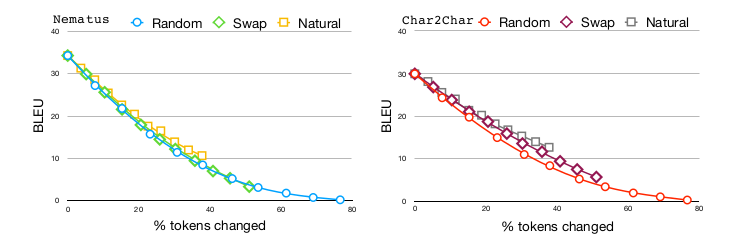

Whatever the language, noise has a striking effect on performance. As a quick note, the results presented in the table aren’t comparable across noise types, since the noise intensity is not the same in all cases. For a fair comparison, have a look at the graphs (German to English): surprisingly enough, the Rand noise isn’t much worse than Swap, despite yielding much more dramatic changes of the tokens. It is actually very surprising, since Swap is strictly included in Rand. This would mean that the NMT model (especially Nematus) is basically unable to recover a word with virtually any Swap mistake. Yet, the authors’ conclusion still holds true:

The important thing to note is that even small amounts of noise lead to substantial drops in performance. […] This is true for both natural noise and all kinds of synthetic noise. […] The degradation in quality is especially severe in light of the humans’ ability to understand noisy texts.

Dealing with noise

Now that we know where we are, what can be done to increase the robustness of our models? The authors propose two natural ideas, and show their effect on performance:

- All models presented rely on word structure to build a representation. This structure is, however, altered to some extent by most of the studied noise types (Swap, Mid, Rand). The idea is therefore to make some architectural modifications in order to learn a representation of words that is invariant to their structure.

- Training on noisy examples has been regularly reported to increase model robustness to noise. Let’s try that too.

Structure invariant representations

As is clear in their architecture, all three of the models under study are by design sensitive to word structure, at a character level (due to convolutional layers or the sub-word units considered). There is a fair chance that a model that is insensitive to this structure would be more robust to noises that affect this structure; nothing groundbreaking there.

Perhaps the simplest such model is to take the average character embedding as a word representation. This model, referred to as meanChar, first generates a word representation by averaging character embeddings, and then proceeds with a word-level encoder similar to the charCNN model.

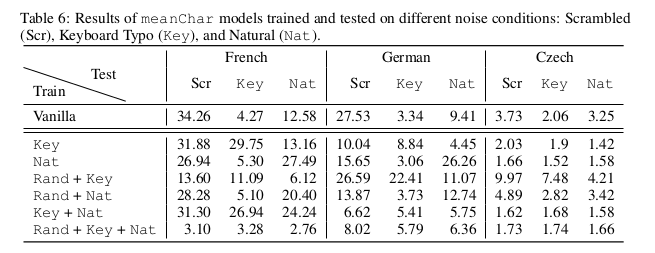

Performance of meanChar in different settings. By design, Scr is the same as Vanilla for this model.

As is clear in the table, meanChar turns out to be pretty good for translating scrambled text (much better than charCNN). Note that, by design, this model sees no difference between vanilla and scrambled texts; the Scr performance reported can therefore be compared to the vanilla performance of other models. However, meanChar is still very sensitive to Nat and Key noise types, that do not resemble Rand.

Personal notes on structure-invariant and graph-based representations

To me, this model seems somewhat coarse. While it is true that averaging all character embeddings removes the reliance on word structure, it also discards a huge part of the information brought by individual character. Unless you are using an embedding dimension that is of the order of the size of your alphabet, the signal transmitted to the convolutional layer dismisses some information about the presence of individual characters, in addition to throwing away all information about order. In other words, not only anagrams will get the same representation, but also some totally different words could by random chance. One could argue that, with a good encoding (e.g. simply using the powers of 2, which is basically cheating by pretending that a full-dimensional one-hot vector can be reduced to a 1-dimensional scalar value), we could always recover the presences; however I cannot think of one that would suit the convolutional structure of the next layer. To be fair, the authors themselves conceded, in a response to a reviewer, that “meanChar may not be the ideal architecture for capturing noise, but it’s a simple, structure-invariant representation that works reasonably well. We have tried several other architectures, including a self-attention mechanism, but haven’t been able to improve beyond it.”

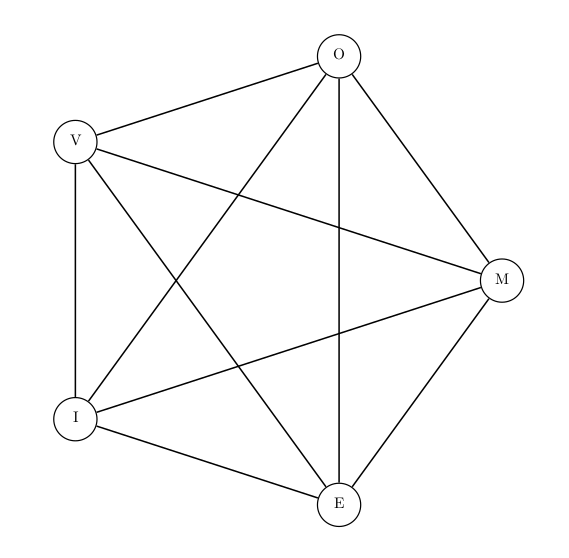

Have a look at Figures 2 and 3 below, depicting the charCNN vs. meanChar word representations. I am pretty sure that a better word representation can be found, discarding only the structure while preserving the presence (instead of “jeter le bébé avec l’eau du bain”, like we say in French). A first thought is a complete graph of individual characters (see Figure 4), with a graph-convolutional layer that would follow. This seems to me like a more natural generalization of the previous models: thinking in terms of graphs where nodes are the characters, previous representations saw a word as a chain of characters, each of them linked only to the next one by a directed edge. Discarding structure would simply mean linking all nodes together by undirected edges.

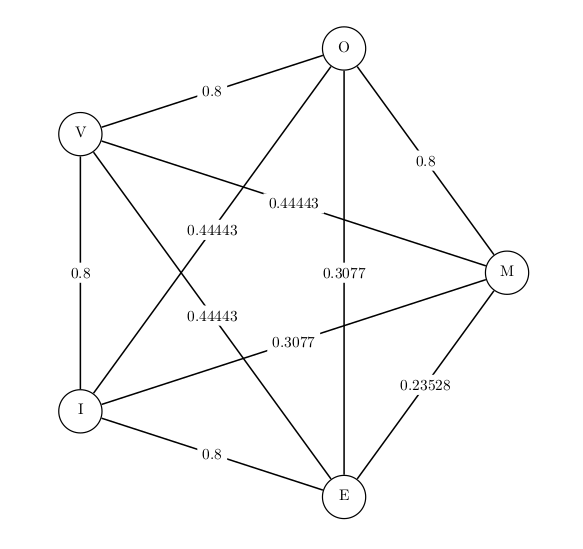

This could even be adapted to retain some weak information about the structure by weighting edges using the original order (the closer two characters in the original word, the higher the weight; see Figure 5). These weights would for example play a role in interaction with regularization, for example $L_2$-regularization on the coefficients of the convolutional filters (for very low weights, it will be too expensive to take those into account unless there is a very good reason). While not completely structure-invariant, this has a potential to make the model more robust to structure change, while retaining all information about the presence of individual characters and not forgetting all about structure like in meanChar.

Figure 2 - charCNN word representation as a chain of character embeddings.

Figure 3 - meanChar word representation as an average of character embeddings.

Figure 4 - graphChar word representation as a complete graph of character embeddings.

Figure 5 - wgraphChar word representation as a weighted graph of character embeddings. The weights, here arbitrary, could reflect the structure to some extent.

Training on noisy texts

Another natural idea is to expose the model to noisy texts during training. I am not too sure that we can adequately call this black-box adversarial training like the authors did, but the concept remains the same: is the model systematically failing to handle a specific type of inputs? Fine, let’s train it on some of these specific inputs, and hope that it has the capacity to learn a relevant pattern.

With meanChar - personal doubts

This is not very convincing. All in all, training on noise type A seems to improve performance when testing on type A noisy texts in French and German, but not in Czech. There is no conclusive result in this table. Note that we didn’t expect meanChar to deal well with Key and Nat noises anyway.

There is however something quite troubling with this table. Remember that meanChar is supposedly invariant to word structure, and should therefore remain unaffected by Rand noise (scrambling), since the model does not make any difference between the original word and the scrambled version. How comes there is such a huge difference in performance between training on Rand+Key and on Key alone? What’s more, this difference is not even consistent across languages. Rand is affecting the training way too much, which means one of the following is wrong: the implementation, the results (including their expected stability), or my understanding of the paper. I’d rather it be the latter.

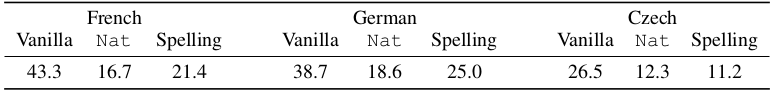

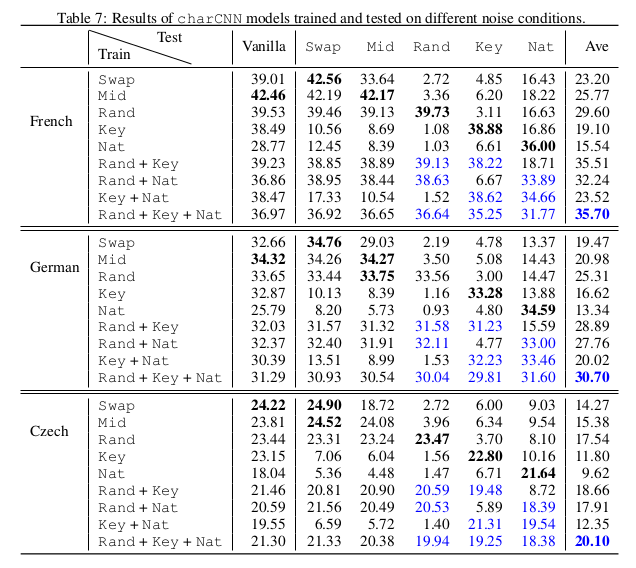

With charCNN - insights on the filters

More extensive experiments show that the more complicated charCNN is, generally speaking, robust to the noise types is was exposed to during training, and only those. Additionally, except when trained on Nat noise alone, all charCNN models keep good performance on vanilla test texts. A model trained on all noise types mixed is not the best in any specific setting, but is the best on average.

From these results, the authors draw three major insights:

- When trained on a mix of different noise types, the charCNN is robust to all noise types that it has been exposed to. In particular, the model trained on Rand+Key+Nat shows good performance in all settings, and gives (according to the authors) a reasonable translation of the Cambridge meme:

-

When trained on synthetic noise, no charCNN model was able to correctly handle natural noise. This is actually a huge problem, since natural noise is what we mostly care about, while synthetic noise is what we can easily generate. More on that in the next section.

-

It is puzzling that, despite the sensitivity of convolutions to the structure of the input, charCNN is able to perform well on scrambled texts when trained on the corresponding noise.

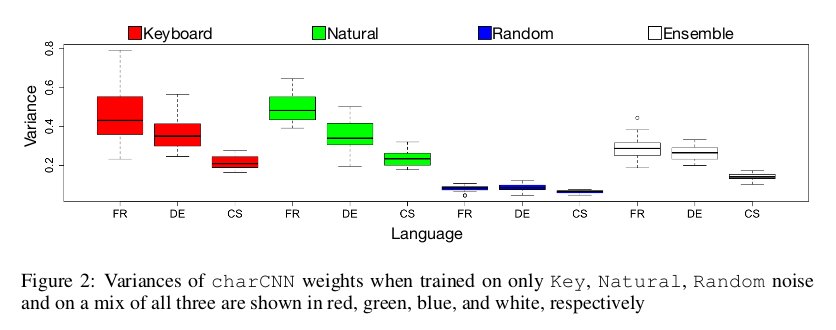

Let us dwell a bit more on the last point. The authors propose an interesting analysis of the convolution filters learned in different settings. They investigate, one dimension (out of the 25 of character embeddings) at a time, what the variance of the weights of the filters are. Their idea is the following: in the scrambled setting, their is no pattern to detect in the character ordering; therefore the variance of weights along a given dimension of the character embeddings should be low, i.e. those weights should lie close to one another.

To test their hypothesis, the authors take, for each filter (out of 1000) and each embedding dimension (out of 25), the variance of the weights across the filter width (6 characters). Intuitively, we expect this variance to be small when the filter is close to being uniform, that is, when the filter is actually performing an average of the embeddings over this specific dimension. They then average these variances across the filters, yielding 25 average variances, which are plotted above.

These results tend to support the hypothesis, although I disagree with the authors’ assertion that “low average variance means that different filters tend to learn similar behavior, while high average variance means that they learn different patterns”. From my understanding, high average variance means that many filters tend to learn a non-uniform pattern, yielding many high individual variances, and a high average. For example, if all filters learned were $[1,2,3,4,5,6]$, the average variance would be equal to the individual variance of $2.9$, which is quite high; nonetheless, all filters learn the same exact pattern. I would also like to note that small variance does not always mean uniform behavior, and that variances can not be so easily compared. For example, if all filters learned were $[0.1,0.2,0.3,0.4,0.5,0.6]$, the variance would be $0.029$, which is much lower than the previous one; yet it is not obvious that the filters learned correspond to a more uniform pattern than the previous case. I doubt however that there is such a scale difference in the actual models trained, so I would buy the authors’ interpretation:

[…] with random scrambling there are no patterns to detect in the data, so filters resort to close to uniform weights. [… Moreover], in the Rand model, the variance of variances [size of the box] is close to zero, indicating that in all character embedding dimensions the learned weights are of small variance; […] the model learned to reproduce a representation similar to the meanChar model.

In the end, a call for better noise

Let’s recap. In the major field of Neural Machine Translation, state-of-the-art models fail to correctly handle even a small amount of noise. This holds true for a variety of noise types, including altering the order of letters in a word, key swapping based on keyboard proximity, and natural noise. While scrambling noise can be correctly handled by structure invariant word representation, such as an average of character embeddings (see the meanChar model), it remains challenging to develop models that are robust to key swapping and natural noise. Training the model on noisy texts yields an increased robustness to the noise types that the model has been exposed to, but decreases general performance, calling for better representations, architectures and understanding of the effect of noise, in order to develop satisfyingly robust models, that could approach human insensitivity to noise in natural language processing.

One point in particular stands out of the paper: natural noise can not be handled by training on synthetic noise. Moreover, it appears that the former qualitatively differs from the latter, being mostly composed of phonological mistakes, character omissions, and incorrect conjugations of verbs. This is a major issue, since natural noise is what we ultimately (in most cases) care about, and synthetic noise is what we are able to easily generate (hence to gather data on). The lack of mechanisms to generate realistic natural human errors in an automatic way remains a huge issue. All in all:

We believe that more work is necessary in order to immune NMT models against natural noise. As corpora with natural noise are limited, another approach to future work is to design better NMT architectures that would be robust to noise without seeing it in the training data.

I personally trust that we will eventually find a good NMT model paradigm that will enable correct translation of both scrambling noise, through structure invariant (or less sensitive) word representation, and key swapping, by integrating a confusion matrix (built from the keyboard) to the character embeddings. However, I think it is still a long way until we find architectures that can handle natural noise without being previously trained on it, so I would vote for algorithms to generate more realistic synthetic noise.